I’ve developed some strange habit of writing a blog entry to completion, finding myself content with organizing my thoughts, and then never pushing Publish… So, let this be the post to break this odd streak:

Three years in and on the tail end of Cherry in the Sky’s creation, it’s only occurred to me how even more amazing certain games I look back fondly on are.

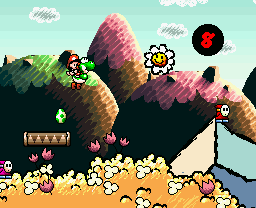

With the greater majority of the levels built, I’ve had to think in a few circles to get down what exactly would constitute higher-level play in Cherry’s game, a 100% run, and it’s brought me to an even greater appreciation of Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, which I think I’ll consider my favorite platforming game of all time.

When attempting a perfect run of anything demanding, there tends to be a natural process: x seconds into challenge > minor perfection ending error > pause > restart. I can’t find any specific praise for how Yoshi’s Island avoids this. The game approaches it a lot like hitting a wrong note while playing a song on guitar: you improvise based off the error and continue jaunting to the end of your solo without anyone noticing, or you’re so talented that what constitutes a mistake to the trained ear, can’t be heard by most. Is that still “perfection”? Perhaps “excellence” would be a better phrase here: “What constitutes player excellence”.

When Yoshi takes a hit, Mario is lost, and your stars function as your timer to return him to your possession before a game over–basically, stars are effectively subtracted when you’re hit. So while the coins and flowers prompt full exploration of the nooks, crannies, and nuances of each world, stars kind of do, but double as your lifebar, which prompts perfect play, a no hit run–however, after being hit and recovering Baby Mario, you could potentially find more stars; obtain a second chance by scavenging to find a “?” cloud filled with them, pound a stake into the ground and find stars underneath, peel and poke at the level in hopes of finding more stars–assuming you can catch the stars once they’re released–assuming you haven’t exhausted all available in the level–assuming you’ll be able to find them if any are still present–assuming you don’t get hit again in the process–this anxious thought process can go on for awhile…

There’s this wonderful, massive gray area over the idea of an ideal run which softens the proposition of perfect play while still retaining the tension. There’s a greater uncertainty than what a standard lifebar can provide, as the difficulty of the situation you lose the baby in can determine how much recovery is necessary, if not resulting in an outright game over, and the further you are into your exploration, the more minimal the errors need to be; playing a song on guitar, you hit a wrong note, but were still in the proper scale, so you swing back into the main melody to work yourself back in line. As long as you put out an excellent performance, you’re golden.

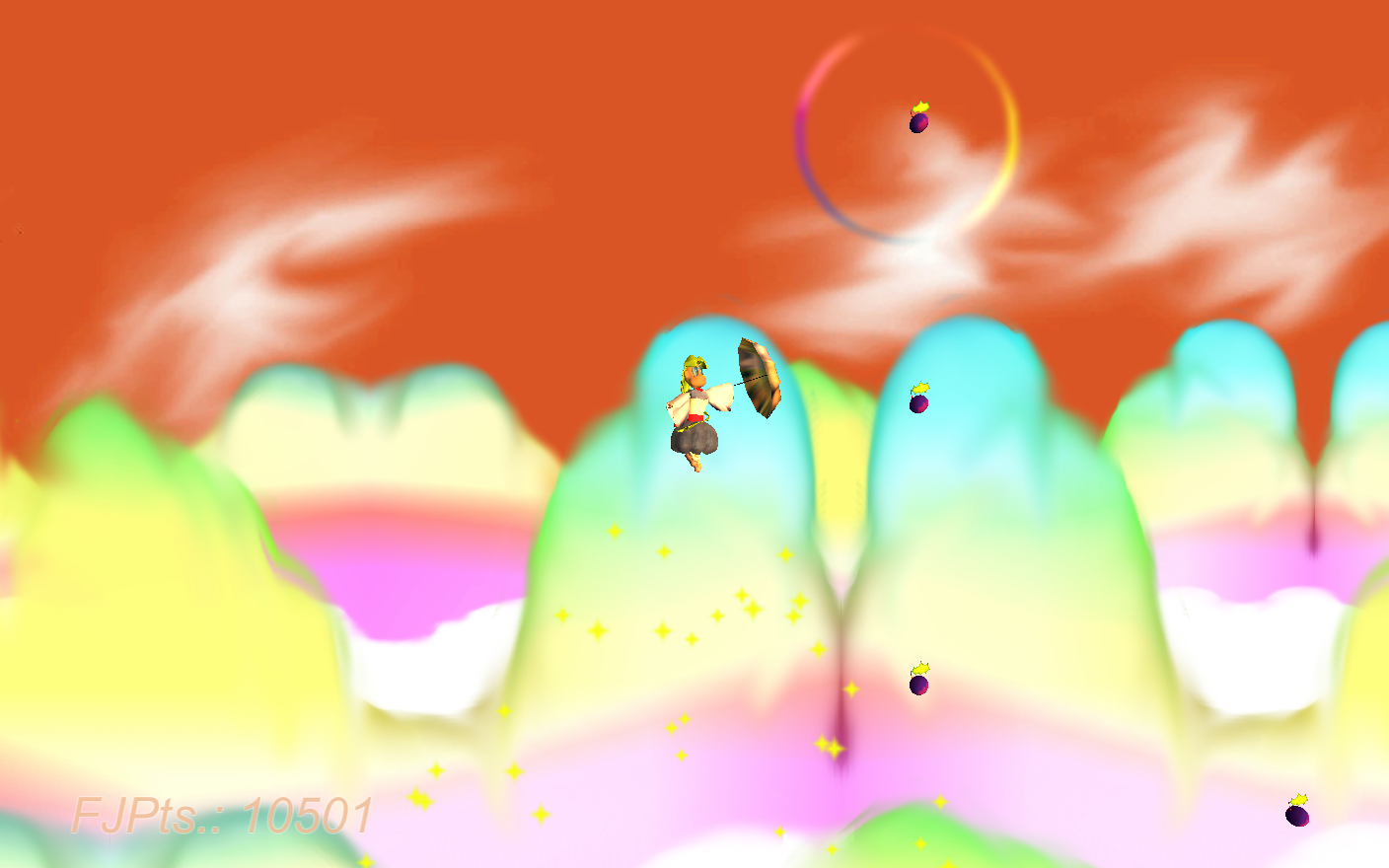

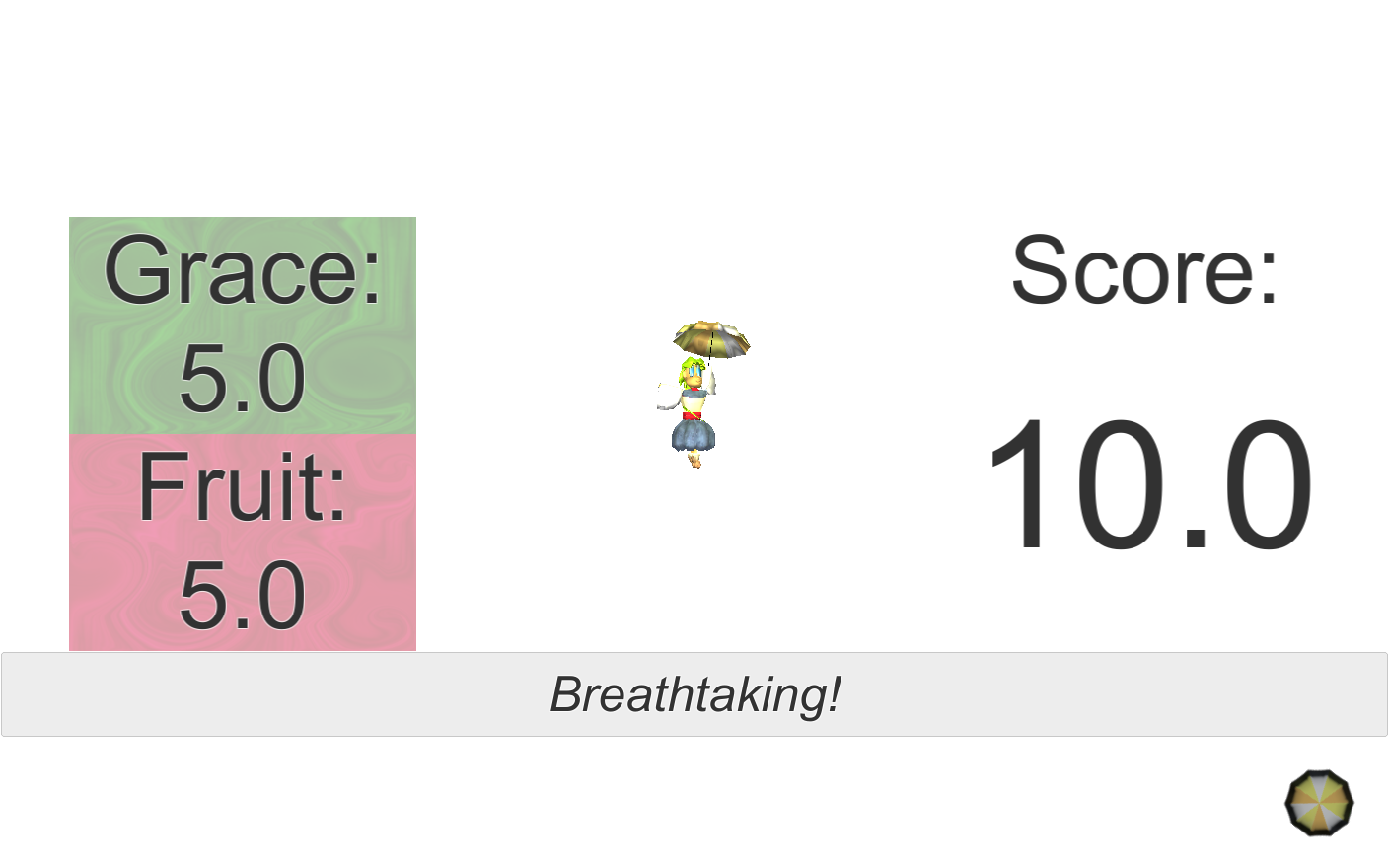

There’s a substantial exhaustive drama to that, a natural excitement. Quick restarts work well in games of frustration (Super Meat Boy being a standout example), but in something slow-paced with lengthier, exploratory sessions like Yoshi’s Island, this is a far more accommodating way of handling “perfection”, one that I’m using as a guide while implementing judgement for player excellence in Cherry in the Sky. I want to take a different approach overall–the verb I’ve been using to describe perfect playthroughs of a Cherry level is “graceful”, while Yoshi’s Island is more “thorough and careful”, like a good parent to Baby Mario, but I do want to gear perfect playthroughs towards “excellence” rather than “perfection”.

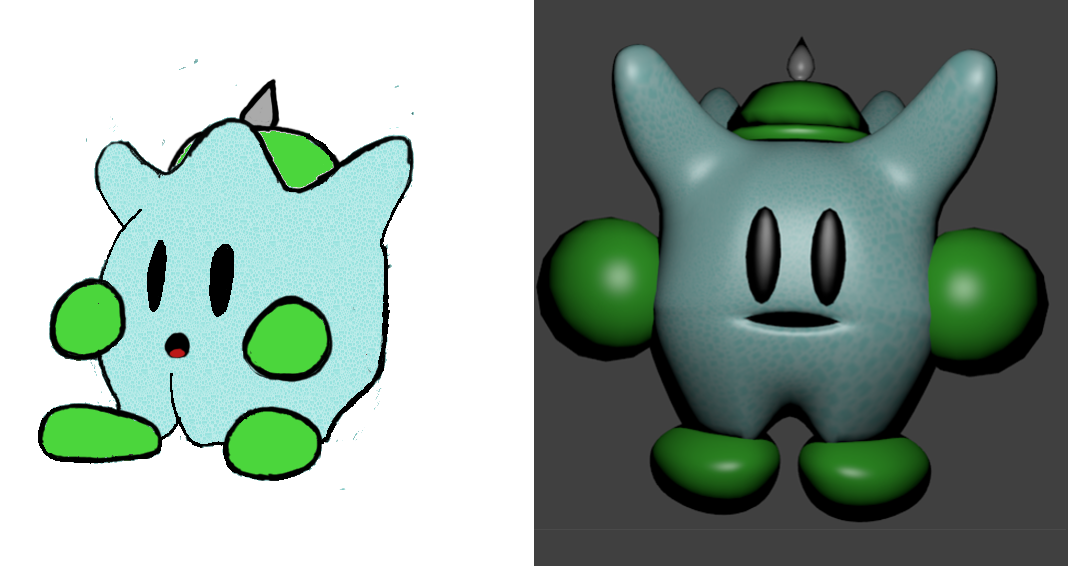

While I feel close to my final system, I realize the way all this is implemented in Yoshi’s Island really reflects the childcare theme, the anxiety caring for a yougin’. So, perhaps the last bits I need to figure out involve diving in deeply into the emotional themes of Cherry in the Sky, honing in on what makes sense for Cherry Sundae as a character–what exactly should constitute excellence for a graceful, hardworking, sky-fruit picking, umbrella-flying farm girl? What sort of judgement would align the player with her goals, opposed to causing dissonance. That’ll probably clear the clouds in front of the answer.