I can’t think of any medium that’s made me angrier than videogames. Board games come close, getting me quite excited, but even then, if a board game is too frustrating, I typically have no desire to play it again. It just sort of “falls off my palette”.

Controller throwing, friend punching, shedding tears as a last boss dances to celebrate his victory. The well-handled presence of upset seems to be an integral part of an affecting videogame–the sense that there is something I want to get, something I want to accomplish, something I need to do, but can’t, wasn’t able to, but still want to: I am frustrated.

Sure, it’s brushed off with silly little death jingles of dark humor as our character explodes or falls off-screen, or maybe the screen just turns red with a quick fade (to make sure it doesn’t so much “hurt” as it “unpleasantly stings”)–either way, this is negative emotion.

Unlike other mediums, the relationship these types of games form with a player is a little more push-and-pull, a little more volatile, a little more like those (manipulative?) how-to dating guides than other creative mediums. You’ve got to shape and play with a person’s desire.

When a novel takes too long to give you what you want, it either gets put down or you suffer through in hopes that something will pull through, right? Any song that frustrates our personal sensibilities just gets turned off. Movies don’t really seem to last long enough to toy with this–sans, perhaps, a frustrating ending, but such a turn is hardly prevalent enough for me call it an integral part of the medium.

A good game should upset you over, and over, and over again.

This is one of your main tools for generating empathy within the game space; it’s one of the ways you align the player with their protagonist, cursor, abilities, etc. You must ensure all good and bad emotions they experience are completely linked within the isolated game experience; no emotion should remain in reality. Your game can never be “real”, but it can evoke 100% percent real feelings.

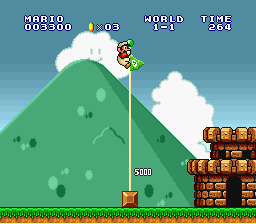

Super Mario never starts you off dying immediately. It usually gives you a few coins, a mushroom, some sort of reward, and then a little easy progress as you advance towards your goal. “I’m getting stuff.” “I’m happy.” Then it starts to ramp up the difficulty, throwing obstacles in your way, more pits, more difficult enemies. It begins to challenge your desire to reach that goal with an opposing force. One that you’re meant to conquer, but one that’s not supposed to be easy. “I’ve done this before. I know I can do it. This is only slightly harder”; it basically wants you to grow to beat it. It is challenging you, and that upset that you are experiencing is you still caring for something you see as possible. (Like those dating guides, right? “Be a challenge”?) This is the distinct difference between something being “challenging” versus plain “too hard”. You’re supposed to win.

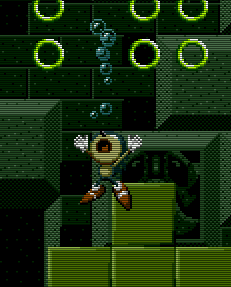

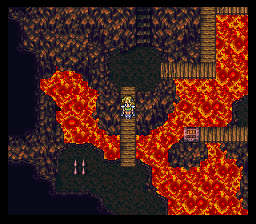

Did anyone ever really like random battles in old-school RPGs? You like a battle system, you like exploring dungeons, but I recall groans of upset and discontent when faced with a random battle when my parties’ supplies were running low. This turned every step towards that treasure hidden through a cavern at the corner of screen something worthy of considerable thought. So despite the spoils of dungeon roving, and the necessity of passing through to advance the story, I often felt them something undesirable as a child–I was actually connecting with the narrative quite deeply. A feeling that aligned me with my character, their mortality, and their goal. They didn’t want to be in those caves either; I can’t remember a single game where the characters unanimously craved roving those dangerous caverns. At least, I didn’t play any.

Given all of this, I guess I would say that Super Mario Bros. is that friend you fought with in grade school, but then went right back to play with the next day, learning, growing, and understanding together. Since the reason for the fight was something stupid you could easily overcome anyway, or at least, when given time to think about it, you realized how capable you were of getting past it to begin with.

The face of gaming has changed substantially since the days of the games I grew up on. It’s not always about enabling or training a player to enjoy your own game anymore… customization options, getting lost in a subscription-based world, getting players into your in-game shop that requires real money, etc.–but the style of games from the period I love are really about only this: training you to succeed, and frustrating you so can enjoy yourself. And apparently, if you balance this just right, you’ll still have people thinking about and playing your game well over two decades later.