I finally understand why I adore this movie. I finally understand why I can watch a man run around a graveyard for a solid three minutes with absolutely no dialogue and be riveted.

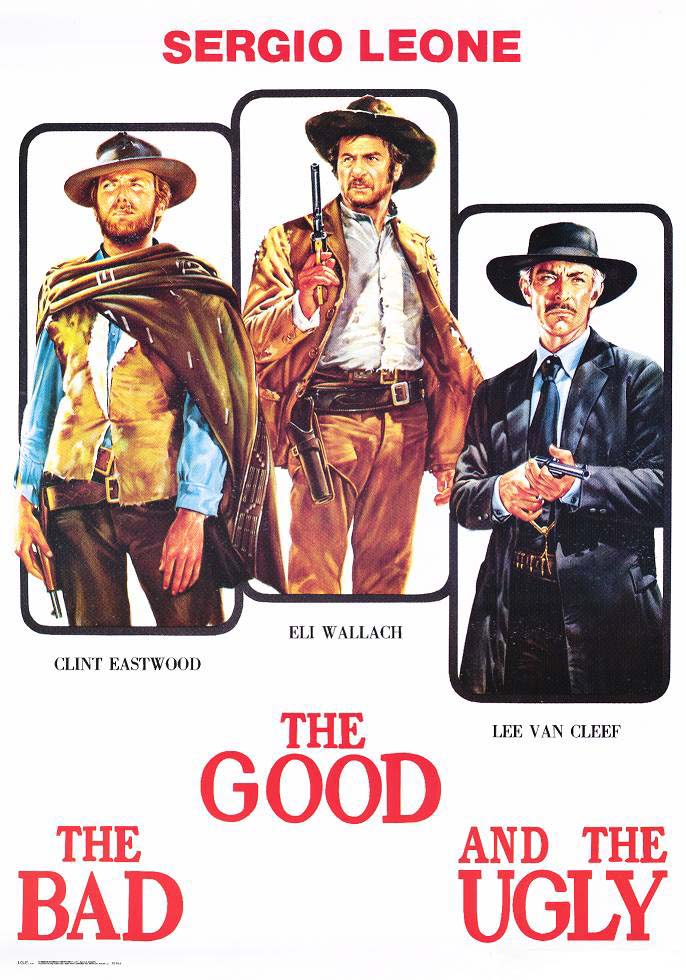

When I often read about The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, I usually hear the fact that it takes place during the Civil War being referred to as the “backdrop” of the movie, and up until recently, I’d overlooked how critical of a component it was myself.

“I’ve never seen so many men wasted so badly,” says Blondie, The Man with No Name, Clint Eastwood’s character, as they observe the Confederate and Union battle at the bridge.

Throughout the entire movie, we experience the war from both ends. The horrible treatment of the opposition, the horrible treatment of ones’ own side, the random senselessness of exploding shells that actually saves characters on occasion. This movie definitely echoes a sort of “war is waste; war is nonsense” sentiment.

Not just war, but greed is there too. It’s never explicitly stated, but both Angel Eyes and Tuco–the Bad and the Ugly respectively–are looking to get wealthy from that healthy sum of money located in the secret grave only Bill Carson knows. However, as shown throughout the entire movie, they just take anything they want from whomever they want anyway. This kind of renders being rich pointless (Tuco completely robs the gun store owner. Angel Eyes begins the movie eating the meal of the man he’s come to kill and is clearly stealing from the camp he’s disguised as a sergeant at).

Angel Eyes is forwarded as pure greed, since he doesn’t have the sympathetic backstory we receive for Tuco (“Where we came from, if one did not want to die of poverty, one either became a priest or a bandit.”). Still, their greed is pretty senseless either way, much like the war. Naturally, Blondie is after the money as well, but he’s never presented as greedy as much as “a realist”. His part in the shooting-the-hanging-Tuco-free scheme is hardly dastardly compared to absolutely everything else presented to the viewer.

But more so than “greed”, and more so than “war”, is “death”. War is killing men on both sides, those seeking Bill Carson’s treasure are killing men on both sides, both men are worried of the other killing the other, countless scenes of men suffering from wounds, dead bodies laying about, death, death, death.

It really hits you. You spend so much time thinking about how everybody’s getting to what they want that you actually don’t give much thought to how much is lost along the way.

The money everyone seeks is buried in a soldier’s grave. When you get to the graveyard, there are so many dead soldiers that finding the grave is an absurd, epic feat. Pointless graves of men who died for near nothing. It’s a waste, and the nonsense reaches its thematic apex when the two protagonists (Tuco is as much a protagonist as he is a villain) blow up the bridge of the nearby battle, and then everyone (confused, frustrated, angry?) still fires on each other. It takes all night before the battlefield clears out and people stop killing. All of this heightens Tuco’s run through the graveyard. It’s what makes it an emotionally affecting three minutes rather than an awkward runabout.

Blondie is the Good here. He is the movie’s anti-hero moral compass, and the final standoff scene is completely under the control of his moral judgement. By the end of it, we actually find out that it was never really a standoff at all.

He overheard Tuco’s upbringing when Tuco spoke with his brother and actually takes pity on the ridiculous fellow (displayed by sharing a cigarette with him shortly after)–Tuco is simply the result of this Ugly world. An unfortunate man, but not an evil one–Blondie never gives him any more or any less than what he’s earned.

In contrast, shortly after being taken along with Angel Eyes, Blondie pretty much directly tells him and his men ‘I’m going to kill you’ when he counts them against the bullets in his gun. He overall disagrees with Angel Eyes’ existence.

Blondie tells the captain of the bridge battle to “keep his ears open”, gives that soldier one last smoke and a little warmth for the final moments of his life–Blondie is the Good because he has a sense of humanity. “Humanity” = “Good” here as much as “Clever” = “Good”.

Being older now, I can pick up on all the nuances in the actor’s performances that convey all this, and how aware all in charge were of the details of their movie.

Angel Eyes is worried during the final standoff (he’s the only one that visibly gulps), and Tuco, always being Tuco, is so confused that he doesn’t know what to think, but both shoot the Bad, but Tuco, being sloppy and whatnot, doesn’t even realize that Blondie has everything taken care of for him due to the empty gun. (Since the viewer is typically confused or surprised, Tuco is actually the easiest character to empathize with. Which is probably a large part of what endears people to him.)

This isn’t a movie that “just happens”. It comes from a lot of people involved understanding the “why” in “what” they’re doing. It being initially universally panned by critics due to being a “genre” piece is kind of comforting. Despite how panned genre fiction was during my creative writing undergrad experience, against my natural desire to write it, I think something like this speaks strongly:

You’re not going to live forever; make whatever you want, and just do it well.